Why the World Cup 2026 Will Be the Most Political Tournament Ever

1) The “first truly continental World Cup” is also a border-and-visa World Cup

The World Cup has always involved travel. But 2026 raises travel to the level of a central plotline.

Three host countries means three immigration regimes, three sets of border politics, and a triangular corridor where many fans will want to follow teams across national lines. That corridor is not neutral territory.

Even before one ball is kicked, the World Cup will be shaped by basic questions:

- Who can get a visa quickly enough to attend?

- Who will be turned away at airports or land crossings?

- Will fans avoid travel out of fear of immigration checks?

- What happens if enforcement actions occur near stadiums?

These aren’t hypothetical concerns invented by critics. Human rights organizations have already warned about the risks of excessive policing and immigration enforcement around venues and major tournaments in North America, and have urged FIFA to obtain guarantees from authorities that matches remain safe for all attendees, including those with precarious immigration status. ()

When an event depends on mass international movement, visa policy becomes a political weapon—or at minimum, a political fault line. Even if governments promise “streamlined travel,” the lived experience of entry screening can vary dramatically by nationality, race, or perceived risk profile. And because 2026 will be enormous—FIFA itself has forecast multi-million attendance—any friction at the border becomes a headline. ()

In earlier World Cups, fans entered one country, dealt with one border system, and stayed largely within it. In 2026, border politics becomes part of the tournament’s architecture.

2) Security, policing, and the fear of “the stadium as a checkpoint”

Mega-events already resemble security operations. The 2026 World Cup will resemble a security operation spread across a continent.

The United States alone has 11 host cities; Mexico and Canada add more. () Each city will coordinate with local police, federal agencies, private security contractors, and—depending on threat assessments—counterterror units.

That creates two political problems:

A) Policing is no longer background—it becomes an experience

When a fan’s “World Cup memory” includes aggressive searches, heavy surveillance, or visible immigration enforcement, the event is no longer just football. It becomes a social conflict about what kind of public space the tournament is creating.

Amnesty International USA and other groups have explicitly flagged the risk that “excessive policing,” including immigration enforcement, could make venues unsafe and undermine the inclusivity FIFA publicly claims to protect. ()

B) Security choices become political messaging

Host governments use mega-events to project power and stability. In 2026, the messaging will be complicated by internal polarization and regional differences: what looks like “public safety” to one audience can look like “militarization” to another. In a World Cup environment, those interpretations spread instantly through social media and global press.

If stadiums begin to feel like checkpoints, the tournament’s legitimacy suffers—and not just morally. It affects attendance, tourism economics, and FIFA’s claim that sport can “bring the world together.”

3) Human rights promises meet a deteriorating political climate

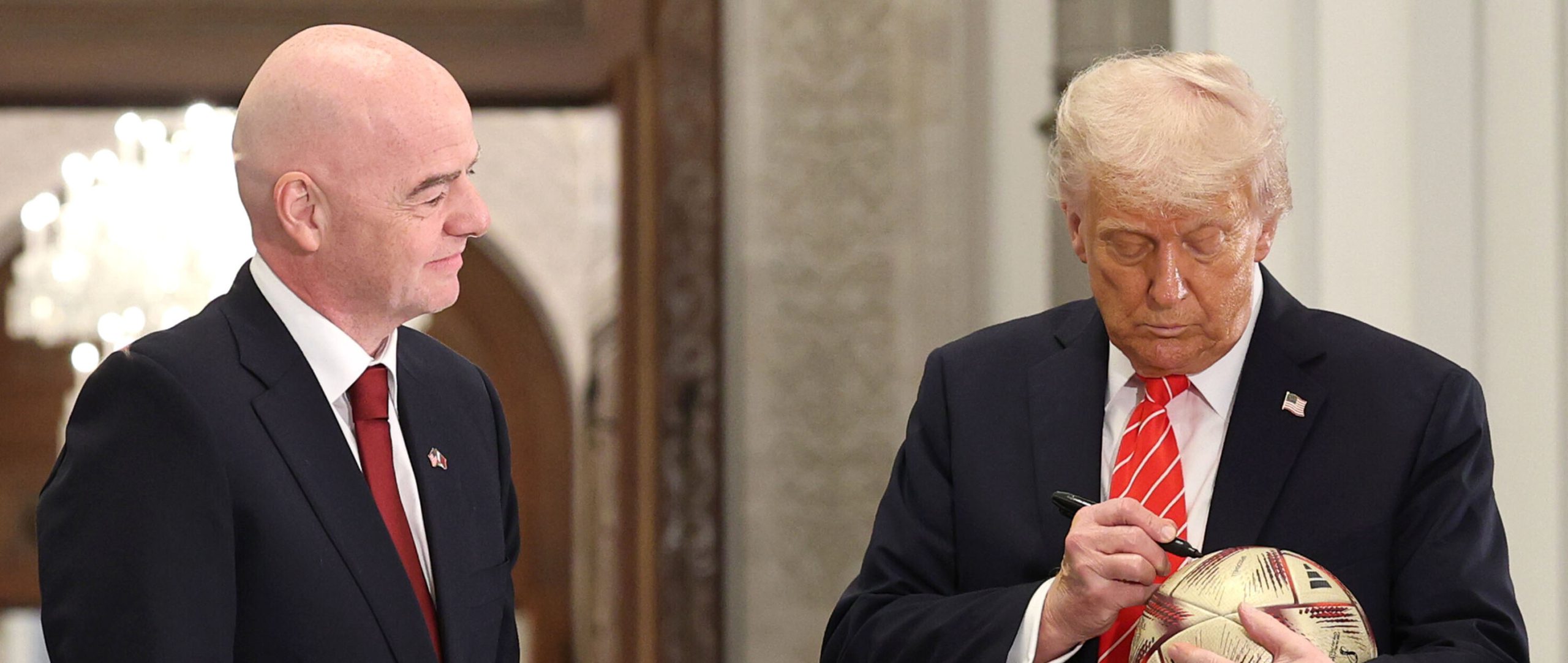

FIFA now talks about human rights more than it did a decade ago. The 2026 bidding process formally included human rights criteria, a response to backlash over prior tournaments. ()

But human rights criteria only matter if they survive contact with reality.

Human Rights Watch has warned that commitments linked to the World Cup can be threatened by changing or deteriorating human rights conditions, including risks affecting workers, communities, athletes, and fans. ()

This matters because 2026 is not one host country with a single, stable political narrative. It’s three hosts, each with its own controversies:

- In the U.S., political debates about migration, policing, protest rights, and discrimination can collide with tournament operations.

- In Mexico, security and organized crime concerns can become part of the global narrative.

- In Canada, issues around policing, indigenous rights, and public order can also enter the frame.

The point isn’t to claim all three countries are “the same.” It’s to note that the World Cup is now being staged in a world where legitimacy is contested constantly and publicly.

In that environment, every policy choice around the tournament can be reframed as a political statement.

4) The “48-team World Cup” is a political economy decision, not just a sporting one

World Cup 26 isn’t merely bigger. It is structurally different: 48 teams and 104 matches. ()

That expansion was marketed as inclusion—more countries, more dreams. But it is also about:

- more inventory for broadcasters

- more commercial rights

- more sponsorship value

- more host-city revenue streams

- more security and logistics contracts

In other words: politics of money.

A bigger tournament increases political stakes. More games mean more chances for protests, more chances for controversies, more travel, more policing, more debate about resource allocation.

And expansion alters football geopolitics too. It changes qualifying and representation across confederations, reshaping which regions gain influence within FIFA’s ecosystem. FIFA has published explanations of the qualification pathways and the expanded tournament structure. ()

In the language of sport, it’s “growth.” In the language of politics, it’s institutional power.

5) Host cities become political arenas

Sixteen host cities means sixteen local political contexts.

Host-city politics will include the predictable battles:

- public spending vs. public services

- stadium upgrades and infrastructure

- housing and short-term rental pressure

- transportation strains

- “clean zones” around venues

- who benefits economically, and who gets displaced

Even a single host city can generate controversies about public money and private profit. Multiply that by 16, across three countries, and the tournament becomes a chain of local political flashpoints.

And since 2026 overlaps with major national narratives (including the U.S. marking the 250th anniversary in 2026, which some host-city coverage already highlights), the World Cup will be embedded in symbolism beyond sport. ()

6) The migrant-worker question doesn’t disappear—it changes form

Qatar 2022 turned labor rights into a defining controversy. Many observers assume that because 2026 hosts are wealthy democracies, labor issues will fade.

That assumption is risky.

The labor politics of 2026 will likely focus on:

- construction and stadium operations

- subcontracting and wage theft risks

- service-sector labor (hotels, catering, event staffing)

- policing and private security labor

- public spending and “temporary” workers

Human rights groups framing the World Cup as dependent on workers and communities suggest that labor and community impacts remain central—even if they look different than in Qatar. ()

And because the U.S., Canada, and Mexico have different labor protections and enforcement, the “weak link” in the system becomes a reputational risk for the entire tournament.

7) Protests: the World Cup as a global stage for domestic anger

Football tournaments draw cameras. Cameras draw movements.

World Cups have repeatedly become stages for protest—sometimes planned, sometimes spontaneous. The political conditions for 2026 make protest likely, because:

- polarization is high

- digital mobilization is faster than ever

- activists understand the value of global attention

- the tournament spans many cities, offering many targets and opportunities

The key political question is not whether protests will occur. It’s how authorities respond—and how those responses are perceived.

If protests are met with heavy-handed policing, the image becomes political. If protests disrupt matches, FIFA becomes political. Either way, the tournament becomes a stage for debates about rights and public order.

8) Information warfare and the platform problem

World Cup 2026 will be the first World Cup fully shaped by the current social platform environment: short-form video virality, algorithmic amplification, and the ease of disinformation.

This changes politics in two ways:

A) Events get reframed instantly

A single video of a confrontation at a stadium gate can travel worldwide in hours, stripped of context and repurposed as propaganda.

B) Nations and political actors can exploit narratives

In a geopolitically tense world, a World Cup spanning North America can be used as an opportunity to portray hosts as chaotic, unsafe, discriminatory—or, conversely, strong and stable.

FIFA can no longer control the story through press conferences. The story is controlled by feeds.

9) Betting, sponsorship, and the regulation gap

Sports betting has become deeply integrated into modern football economies. The World Cup, with its massive global audience, is a magnet for betting operators.

That opens another political front:

- regulation differs across the U.S., Canada, and Mexico

- advertising rules vary

- concerns about addiction and match integrity intensify

- sponsorship optics become contentious

This matters because betting debates tend to turn moral quickly. They collide with public health narratives, youth protection, and “who profits from sport.”

For a tournament already facing scrutiny over policing and rights, betting controversies can feel like yet another example of football’s commercial machine overtaking its cultural role.

10) FIFA vs. governments: who really runs the World Cup?

Mega-events involve constant negotiation between FIFA and host governments. FIFA demands:

- tax exemptions

- commercial exclusivity zones

- brand protections

- security guarantees

Host governments want:

- tourism and prestige

- economic uplift

- political capital

That relationship is inherently political: it’s about sovereignty, money, and control.

In 2026, with three hosts, the negotiation becomes even more complex—because FIFA will want consistent guarantees, but legal systems and political appetites vary.

This is where “the World Cup is apolitical” myth collapses. The event requires political power to function at scale.

11) The schedule itself reflects power

Even the distribution of matches can be politically sensitive: which cities get marquee games, which regions see their teams play nearby, and how travel burdens fall on certain fan bases.

FIFA publishes host-city information and match scheduling details through official channels. ()

In a three-nation tournament, scheduling decisions can become symbolic. A match in one city can be framed as “reward” or “snub.” Final-stage matches become prestige assets, and prestige assets are political currency.

12) Boycotts and symbolic participation debates won’t disappear

Boycotts are rare in modern football, but the talk of boycotts is not. As politics intensify, public figures in football increasingly raise questions about whether participation confers legitimacy on host policies.

Even recent commentary in European football circles has floated boycott discussions in response to geopolitical tensions, illustrating how quickly World Cup participation can become a political argument. ()

The larger point: 2026 is happening in an era when sports institutions are repeatedly asked to “take a stand”—and when taking no stand is interpreted as a stand.

13) The World Cup is now a test of democratic credibility

For much of the 20th century, mega-events were seen as proof of organizational competence. In the 21st century, they increasingly look like stress tests.

World Cup 2026 will test:

- whether rights promises are enforceable

- whether policing can remain proportional

- whether border systems can accommodate global fandom

- whether disinformation can be contained

- whether public spending yields public benefits

And because the hosts include the United States, the tournament will be read globally as a statement about the state of American governance—particularly around security, immigration, and civil liberties.

That is politics, whether FIFA likes the word or not.

14) Why this tournament—more than any other—will be experienced as political

Many World Cups have been political:

- Argentina 1978 under military dictatorship

- USA 1994 amid American culture wars

- Russia 2018 under geopolitical scrutiny

- Qatar 2022 under human rights criticism

So why might 2026 feel more political than all of them?

Because it combines:

- continental scale (three nations, 16 cities) ()

- record commercial and logistical footprint (48 teams, 104 matches) ()

- a global rights-and-policing spotlight (explicit calls for guarantees) ()

- a border politics environment where mobility itself is contested ()

- a post-trust information ecosystem where narratives travel faster than facts

This isn’t just “sport plus politics.” It’s sport occurring inside political systems that are already strained.

15) What to watch as the tournament approaches

If you want to cover 2026 like a serious journalist—or publish analysis that will actually age well—watch these five areas:

1) Immigration and visa policy announcements

Any tightening, selective enforcement, or high-profile incident will become global news.

2) Security planning and inter-agency coordination

Look for formal agreements, guarantees, and transparency about policing boundaries.

3) Human rights guarantees demanded from FIFA and hosts

Organizations have already called for binding commitments; whether they materialize matters. ()

4) Host city economics

Watch for housing pressure, price spikes, and the politics of “who benefits.”

5) Online manipulation and disinformation campaigns

Expect “security panic” narratives and politicized clips engineered for outrage.

Closing: the World Cup as a mirror, not an escape

FIFA sells football as a break from reality. But the 2026 World Cup will likely function as something else: a mirror that reflects reality back at a global audience.

Because your ability to attend, to move freely, to feel safe, to protest, to be treated equally at a gate—these are not sporting questions.

They are political ones.

World Cup 2026 will still give us football: joy, heartbreak, drama, myth-making. But around the matches, another competition will unfold: between openness and restriction, inclusion and enforcement, commercial spectacle and public rights.

And that is why, long after the trophy is lifted, many will remember 2026 not only for who won—but for what kind of world hosted it.

#worldcup #worldcup2026 #football #politics #usa #mexico #canada